Globalisation has gotten a bad press in the West recently, with the failure of governments to prevent citizens from being left behind seen as the root of much recent political turmoil – not least the election of Donald Trump.

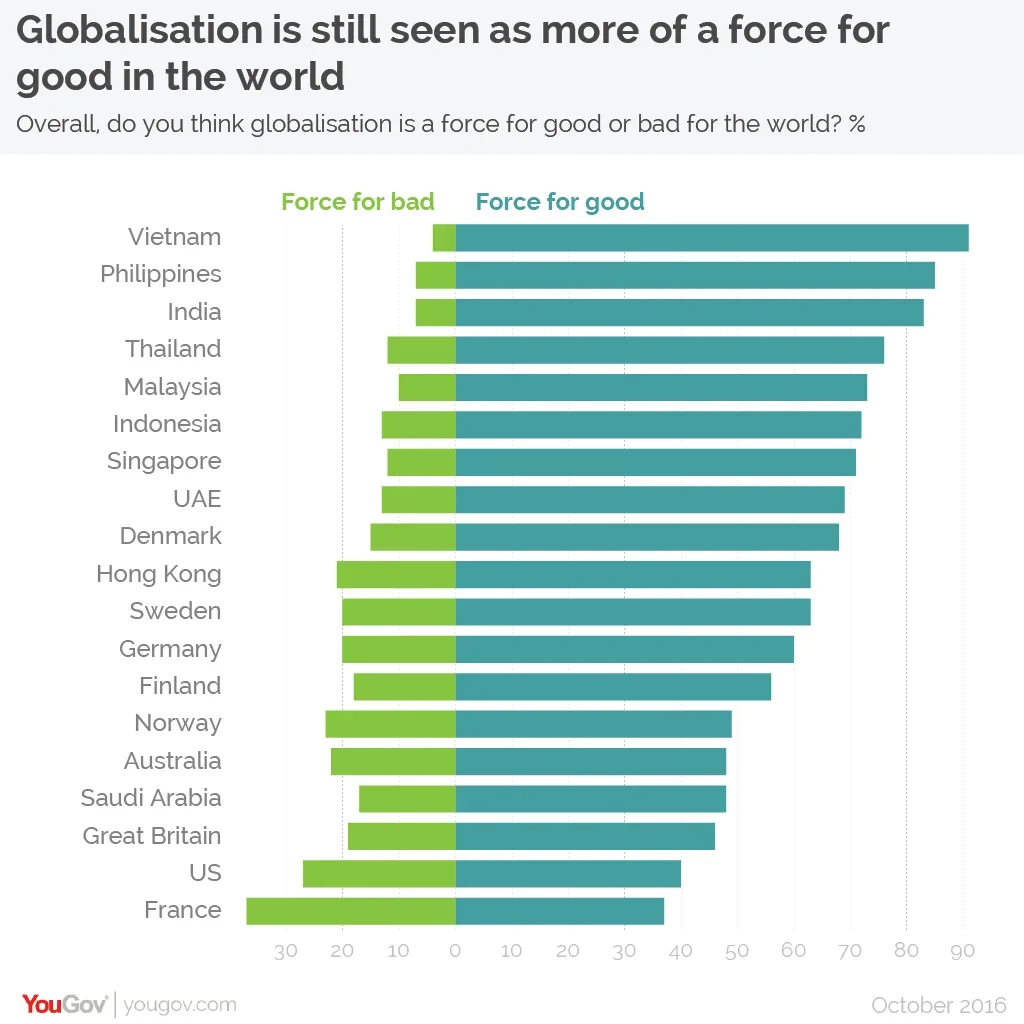

Nonetheless, a new YouGov survey of more than 20,000 people across 19 countries finds that in almost all of them people are more likely to think that globalisation has been a force for good rather than ill – and by wide margins.

Unsurprisingly, the countries that are the biggest enthusiasts of globalisation are the ones that have benefitted most from it – the poorer nations of East and South East Asia. Here, belief that globalisation is a force for good reaches at least 70% in all countries, and as high as 91% in Vietnam.

Support is still strong in Europe though (with the exception of France – more of which later), with around half or more of people in the countries surveyed saying that globalisation has been a force for good.

There is, however, widespread acknowledgement that the rich have been the main beneficiaries of globalisation. In every single country, far more people agreed than disagreed that the wealthy have benefitted more from globalisation than ordinary citizens.

Scratching beneath the surface

Whilst citizens across the world might be relatively warm to globalisation as a concept, delving deeper into its individual components reveals a much more mixed response.

Take interdependence, for instance. In a connected world where the manufacture of everyday products is so complex that the supply lines involved in creating them span the globe, it is inevitable that countries must trade with one another in order to meet their own needs. Nevertheless, as many as 78% of Indonesians think that their country should be able to meet its own needs without having to rely on imports from other countries. So do 57% of Indians, 53% of Filipinos and 52% of French people.

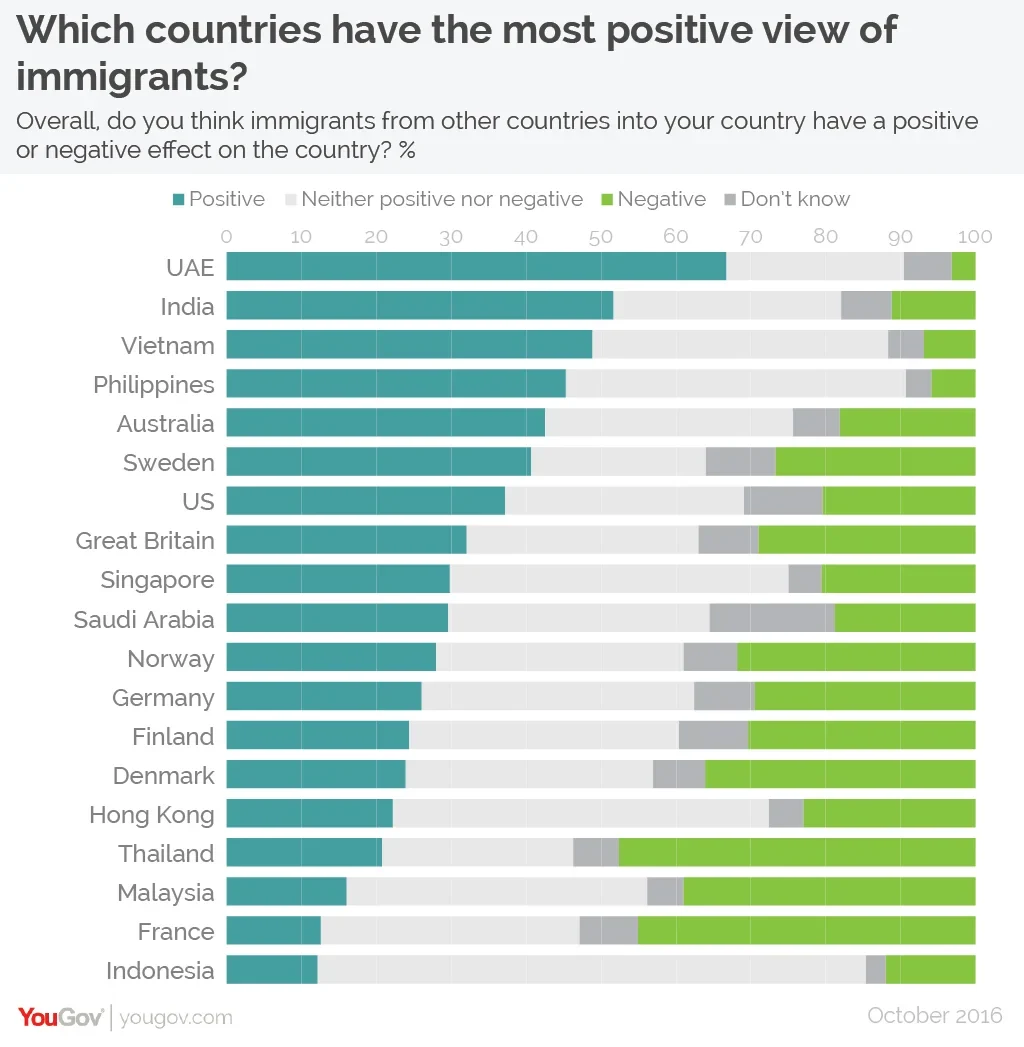

Likewise, questions on immigration reveal another mixed picture – even among neighbours. In the Phillipines, 45% of people believe that immigrants have a positive effect on the country, and just 6% a negative one. In neighbouring Malaysia, just 16% have a positive image of immigrants and 39% a negative one, whilst in Indonesia a full 73% of people consider their impact to be neither positive nor negative.

Arrêter le monde

The most striking revelation of the survey is the extent of French disillusionment with globalisation. In six of the survey’s 11 questions, French people displayed the most negative sentiment towards globalisation (measured in net terms). They came near the bottom in several others.

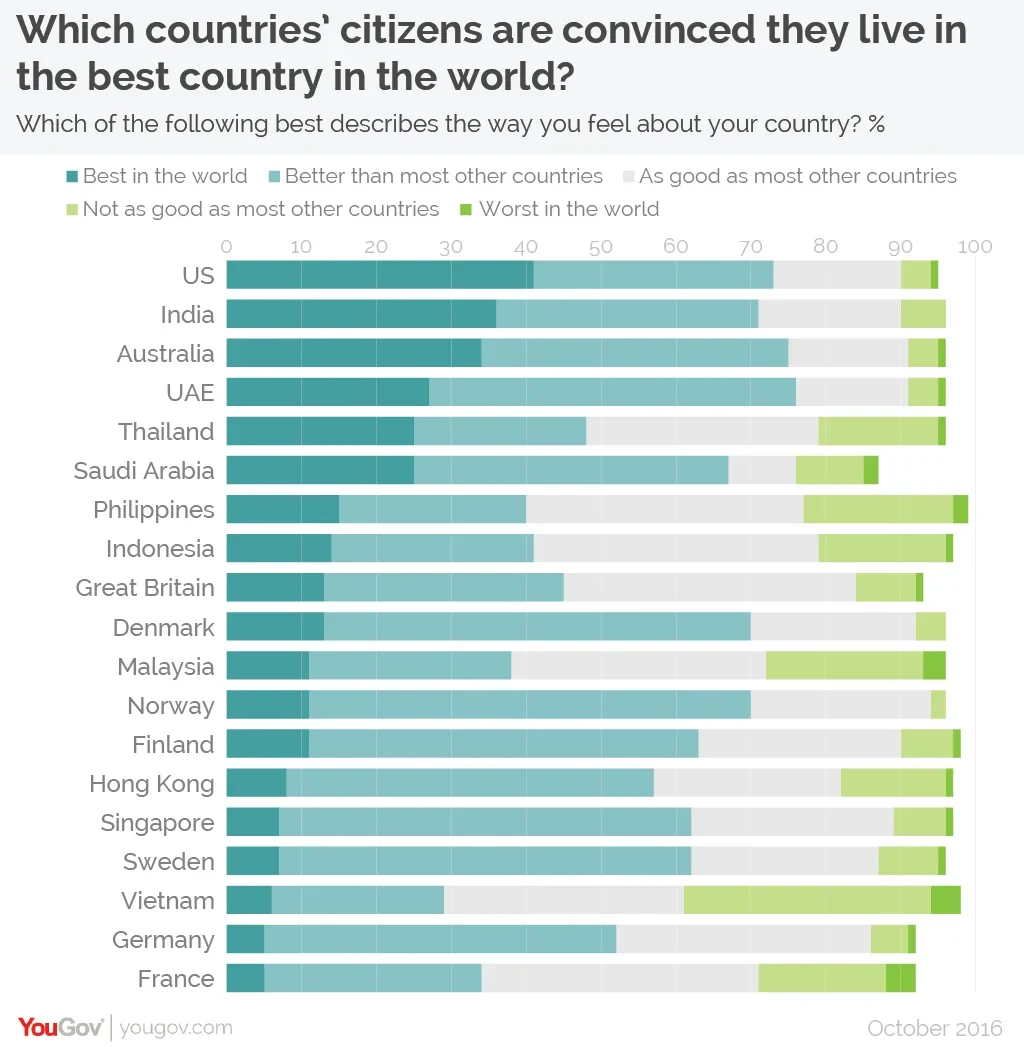

This disillusionment extends to their view of their own country – as many as 21% of French people think that France is worse than most other countries, a figure more comparable to the developing nations on the survey rather than the developed nations. The 4% of French people who think France is the worst country in the world is the joint-highest rate on the survey (with Vietnam) – French people are also the least likely to say they live in the best country in the world.

This is all very bad news for those who fear a victory for the far right in France’s upcoming presidential and parliamentary elections – not least when coupled with the results of a major new YouGov study showing that 63% of French voters hold “authoritarian populist” views.

If there is hope, it lies in the young

It may be too late for anyone to alter the near-term course of French history, but there is a glimmer of hope for globalists in the longer term. Whilst 37% of French people overall say that globalisation is a force for good, this figure is as high as 77% among 18-24 year olds. Younger people having a more positive opinion of globalisation than their older peers is a pattern repeated across the world.

The obvious question is whether these younger people will carry their views with them as they age, or if they grow out of them as they get older. If it does turn out that the values of globalisation have been firmly embedded in the young, then the current backlash against globalisation may turn out to be nothing more than an aberration in the onward march of history.